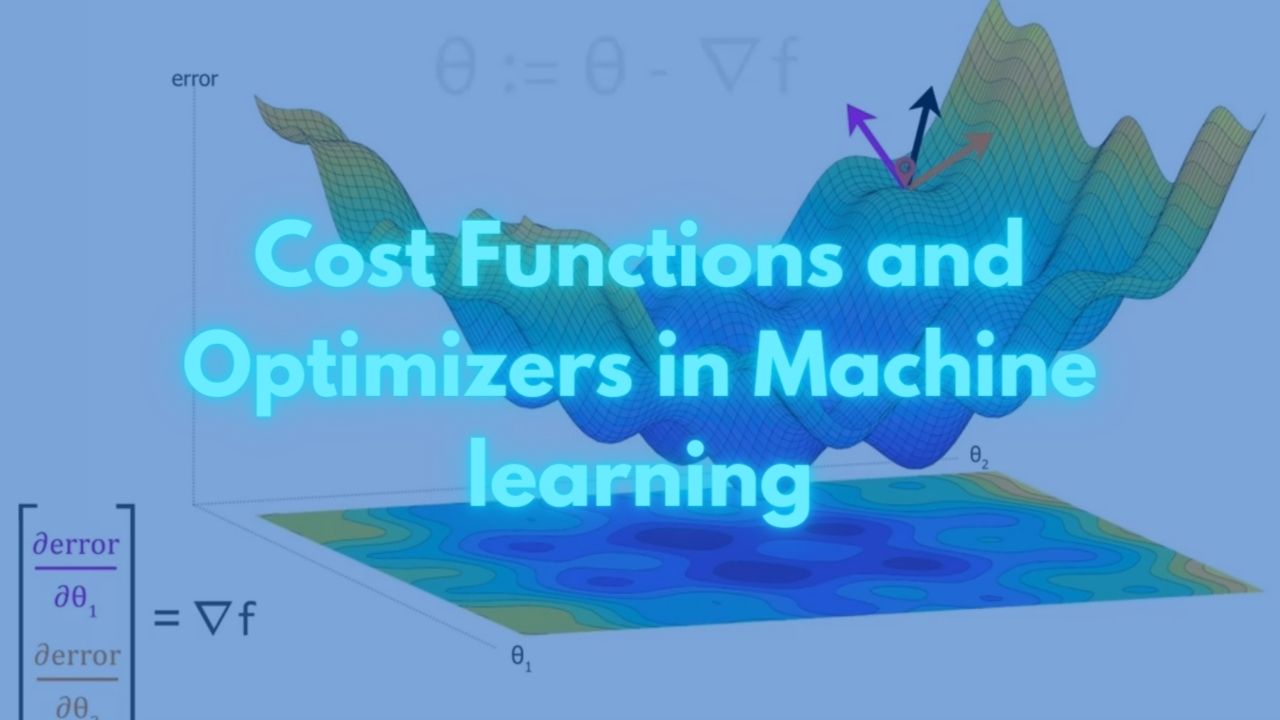

Cost-Functions-and-Optimizers-in-Machine-Learning#

What is machine learning?#

Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence that focuses on the development of algorithms and statistical models that enable computers to improve their performance on a specific task through experience.

In machine learning, the goal is to develop models that can automatically learn patterns and relationships in data, and use that knowledge to make predictions or take actions. The models are trained on a large dataset, and the learning process involves optimizing the parameters of the model to minimize the prediction error. For this purpose every algorithms uses some cost function or loss function.

There are various types of machine learning, including supervised learning, unsupervised learning, semi-supervised learning, and reinforcement learning. These approaches are used in a wide range of applications, including image classification, speech recognition, natural language processing, recommendation systems, and predictive analytics.

What is cost function?#

A cost function, also known as a loss function or objective function, is a mathematical function that measures the difference between the predicted output of a model and the actual output. The cost function is used to evaluate the performance of a machine learning model and guide the optimization process during training.

The goal of training a machine learning model is to minimize the value of the cost function. This is achieved by adjusting the parameters of the model to reduce the prediction error. The choice of cost function will depend on the type of problem being solved and the type of model being used.

For example, in a binary classification problem, a common cost function is the cross-entropy loss, which measures the difference between the predicted probabilities and the actual class labels. In a regression problem, a common cost function is the mean squared error, which measures the average squared difference between the predicted values and the actual values.

The cost function provides a measure of the model’s performance, and the optimization process aims to find the values of the model’s parameters that minimize the cost function. The optimization process is usually performed using gradient descent or other optimization algorithms, which iteratively update the parameters to reduce the value of the cost function.

What is the difference between loss function and cost function?#

The terms “cost function” and “loss function” are often used interchangeably, but they do have subtle differences depending on the context:

1. Loss Function:#

- Definition: A loss function measures the error for a single training example. It quantifies how well the model’s prediction matches the actual target value for that particular example.

- Use Case: Typically used in contexts where you’re evaluating or updating the model on a per-example basis.

- Example: In a binary classification task, if your model predicts the probability of a sample belonging to the positive class, the loss function might be binary cross-entropy, which compares this prediction to the actual class label.

2. Cost Function:#

- Definition: A cost function is generally the average (or sum) of the loss functions over an entire dataset. It provides a measure of the overall model performance across all training examples.

- Use Case: Used during the training process to evaluate and minimize the overall error of the model.

- Example: The cost function could be the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for a regression task, which is the average of the squared errors (individual losses) over all the training examples.

Summary of Differences:#

Scope:

- Loss function is usually focused on a single data point.

- Cost function aggregates the loss across all data points in the dataset.

Usage:

- The term “loss function” is more commonly used when referring to the error for individual predictions.

- The term “cost function” is often used when referring to the total error used to train the model (e.g., in optimization algorithms).

Example in Practice:#

- Loss Function: If you’re using Mean Squared Error as your loss function, then for each training example, the loss might be calculated as: $$ \text{Loss} = (y_{\text{true}} - y_{\text{pred}})^2 $$

- Cost Function: The cost function would then be the average of these losses across all examples: $$ \text{Cost} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_{\text{true, i}} - y_{\text{pred, i}})^2 $$

In summary, the loss function is a measure of error on a single data point, while the cost function is a measure of error across the entire dataset.

The specific form of the cost function will depend on the type of problem being solved and the nature of the output variables. For example, in regression problems, the mean squared error (MSE) is often used as the cost function, while in classification problems, the cross-entropy loss is commonly used.

What are different cost functions?#

Cost functions, also known as loss functions, are mathematical functions used in machine learning to quantify the difference between the predicted output of a model and the actual target values. The goal of training a model is to minimize this cost function, thereby improving the model’s performance. Common Cost Functions:

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- Description: Measures the average squared difference between predicted values and actual values.

- Formula: $$ \text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 $$ where $$ y_i $$ is the actual value, $$ \hat{y}_i $$ is the predicted value, and $$ n $$ is the number of data points.

- Use Case: Commonly used in regression tasks.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- Description: Measures the average absolute difference between predicted values and actual values.

- Formula: $$ \text{MAE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} |y_i - \hat{y}_i| $$

- Use Case: Used in regression tasks, particularly when outliers are less influential.

Binary Cross-Entropy (Log Loss)

- Description: Measures the difference between predicted probabilities and actual binary labels. It penalizes incorrect predictions more heavily.

- Formula: $$ \text{Binary Cross-Entropy} = -\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i \log(\hat{y}_i) + (1 - y_i) \log(1 - \hat{y}_i) \right] $$

- Use Case: Used in binary classification tasks.

Categorical Cross-Entropy

- Description: Measures the difference between the predicted probability distribution and the actual one-hot encoded target distribution.

- Formula: $$ \text{Categorical Cross-Entropy} = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{k} y_{ij} \log(\hat{y}_{ij}) $$ where $$ k $$ is the number of classes, and $$ y_{ij} $$ is the actual one-hot encoded value.

- Use Case: Used in multi-class classification tasks.

Huber Loss

- Description: Combines MSE and MAE, offering a balance between the two. It is less sensitive to outliers than MSE.

- Formula: $$ \text{Huber Loss} = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 & \text{for } |y_i - \hat{y}_i| \leq \delta \ \delta \cdot |y_i - \hat{y}_i| - \frac{1}{2} \delta^2 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$ where $$ \delta $$ is a threshold.

- Use Case: Used in regression tasks, especially when dealing with outliers.

Hinge Loss

- Description: Used for “maximum-margin” classification, such as SVMs. It penalizes predictions that are on the wrong side of the decision boundary or within a margin.

- Formula: $$ \text{Hinge Loss} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \max(0, 1 - y_i \cdot \hat{y}_i) $$ where $$ y_i $$ is the true label (-1 or 1) and $$ \hat{y}_i $$ is the predicted output.

- Use Case: Used in Support Vector Machines (SVM) for binary classification.

Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence

- Description: Measures the divergence between two probability distributions, often used as a regularization term in models like VAEs.

- Formula: $$ \text{KL Divergence} = \sum_{i} P(x_i) \log \frac{P(x_i)}{Q(x_i)} $$

- Use Case: Used in probabilistic models, VAEs, and reinforcement learning.

Poisson Loss

- Description: Used for count data and assumes that the target variable follows a Poisson distribution.

- Formula: $$ \text{Poisson Loss} = \hat{y}_i - y_i \log(\hat{y}_i) $$

- Use Case: Used in models where the target variable represents counts.

Cosine Similarity Loss

- Description: Measures the cosine of the angle between two non-zero vectors, indicating their similarity.

- Formula: $$ \text{Cosine Similarity Loss} = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_i \hat{y}i}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n} y_i^2} \cdot \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \hat{y}_i^2}} $$

- Use Case: Used in tasks like text similarity, recommendation systems, and face recognition.

Wasserstein Loss

- Description: Used in Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) to measure the distance between the real data distribution and the generated data distribution.

- Formula: Depends on the specific WGAN implementation but generally involves the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD).

- Use Case: Used in GANs to improve training stability and address issues like mode collapse.

Different cost functions are chosen based on the type of problem (regression, classification, etc.) and the specific characteristics of the data (e.g., presence of outliers). The goal is to find a cost function that aligns well with the task and helps the model converge to an optimal solution during training.

What are different cost functions for different Machine learning goals?#

Cost Function for Regression#

If the goal is Regression, we want to predict a continuous number, then we can use use these cost/loss functions.

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): used for regression problems, measures the average squared difference between the predicted output and the actual output.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): also used for regression problems, measures the average absolute difference between the predicted output and the actual output.

- Huber Loss: a combination of mean squared error and mean absolute error, used for robust regression.

- Smooth L1 Loss: also known as the Huber Loss, a combination of mean squared error and mean absolute error, used for object detection in computer vision.

- Log-Cosh Loss: a smooth approximation of the mean absolute error, used for regression problems.

Cost Function for Classification#

If the goal is Classification, we want to predict a class/category, then we can use use these cost/loss functions.

- Binary Cross-Entropy Loss: a variation of cross-entropy loss, used for binary classification problems.

- Cross-Entropy Loss: measures the difference between the predicted class probabilities and the actual class label, used for multi-class classification problems.

- Hinge Loss: used for maximum-margin classification problems, measures the margin between the predicted class and the incorrect class.

- Squared Hinge Loss: a variation of hinge loss, used for maximum-margin classification problems.

- Multi-Class Logarithmic Loss: used for multi-class classification problems, measures the average log loss across all classes.

- Focal Loss: used for object detection in computer vision, adds a term that modulates the cross-entropy loss based on the prediction confidence.

- Categorical Cross-Entropy Loss: another variation of cross-entropy loss for multi-class classification problems.

Cost Function for Clustering#

If the goal is Clustering, we want to group samples/records/examples, then we can use use these cost/loss functions.

- Sum of Squared Errors (SSE): measures the sum of squared differences between each data point and its nearest cluster center.

- Within-Cluster Sum of Squared Errors (WCSS): similar to SSE, but measures the sum of squared differences between each data point and its nearest cluster center, averaged across all clusters.

- Davies-Bouldin Index: measures the similarity between each pair of clusters, based on the distance between their cluster centers and the size of their cluster.

- Silhouette Score: measures the similarity between each data point and its own cluster compared to other clusters.

- Calinski-Harabasz Index: measures the ratio of between-cluster variance to within-cluster variance, based on the sum of squared differences from the cluster centers.

Cost Function for Sementic Segmenration#

If the goal is Semantic Segmentation (a type of image analysis task in computer vision where the goal is to classify each pixel in an image into a predefined category or class.), then we can use use these cost/loss functions.

- Cross-Entropy Loss: measures the difference between the predicted class probabilities and the actual class label.

- Dice Loss: measures the overlap between the predicted and ground-truth segmentation masks.

- Intersection over Union (IoU) Loss: similar to Dice loss, measures the overlap between the predicted and ground-truth segmentation masks, but normalizes the overlap based on the size of the masks.

- Jaccard Loss: a variant of IoU loss, which measures the overlap between the predicted and ground-truth segmentation masks.

- Focal Loss: adds a term that modulates the cross-entropy loss based on the prediction confidence, which can improve the performance of the model on the hard examples.

Cost Function for Text Genration#

Can you tell what different loss functions are available to update the parameters during learning in Text Generation models?

In text generation models, various loss functions are used to update the model’s parameters and improve performance. The choice of loss function depends on the model architecture and the specific text generation task. Here are some common loss functions used in text generation:

1. Cross-Entropy Loss (Negative Log-Likelihood Loss)#

- Description: Measures the difference between the predicted probability distribution over the vocabulary and the actual target distribution (one-hot encoded vector).

- Use Case: Used extensively in sequence-to-sequence models, language models, and other text generation tasks where the goal is to predict the next token in a sequence.

- Formula: $$ \text{Cross-Entropy Loss} = -\sum_{i=1}^{N} \log P(y_i | x) $$ where $$ y_i $$ is the actual token and $$ P(y_i | x) $$ is the predicted probability of the token given the input $$ x $$.

2. Reinforcement Learning-Based Loss (Policy Gradient)#

- Description: Used when the text generation model is trained using reinforcement learning techniques, such as the REINFORCE algorithm. The loss is based on the reward signal received from the environment or from a discriminator in GANs.

- Use Case: Used in models like SeqGAN, where text is generated in sequence and evaluated based on a reward function rather than direct supervised labels.

- Formula: $$ \text{Policy Gradient Loss} = - \mathbb{E}[R(\tau) \log \pi_\theta(\tau)] $$ where $$ R(\tau) $$ is the reward associated with the generated sequence $$ \tau $$, and $$ \pi_\theta $$ is the policy (model) with parameters $$ \theta $$.

3. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) Loss#

- Description: A loss function that maximizes the likelihood of the observed data given the model parameters. It’s closely related to cross-entropy loss in the context of text generation.

- Use Case: Common in sequence generation tasks where the objective is to maximize the probability of the training sequences.

- Formula: $$ \text{MLE Loss} = -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \log P(y_t | y_{<t}, x) $$ where $$ yt $$ is the target token at time step $$ t $$, and $$ y{<t} $$ represents the previous tokens.

4. Perplexity#

- Description: Perplexity is not a direct loss function but a metric derived from cross-entropy loss. It measures how well a probability distribution or probability model predicts a sample.

- Use Case: Used as an evaluation metric for language models, lower perplexity indicates a better model.

- Formula: $$ \text{Perplexity} = 2^{\text{Cross-Entropy Loss}} $$

5. KL Divergence (Kullback-Leibler Divergence)#

- Description: Measures the divergence between the predicted distribution and a target distribution. It’s often used in variational autoencoders (VAEs) for text generation.

- Use Case: Regularizes models to ensure that the generated distribution doesn’t diverge too far from a prior distribution.

- Formula: $$ \text{KL Divergence} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} P(y_i | x) \log \frac{P(y_i | x)}{Q(y_i)} $$ where $$ P(y_i | x) $$ is the predicted probability and $$ Q(y_i) $$ is the target probability.

6. BLEU Score-Based Loss#

- Description: BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) is a metric used to evaluate the quality of text generated by comparing it with reference texts. Some approaches involve directly optimizing BLEU or using it as a reward in reinforcement learning.

- Use Case: Used in machine translation and other generation tasks where the quality of the generated text relative to reference text is important.

- Formula: BLEU is not directly a loss function, but can be used as a reward signal: $$ \text{BLEU} = \text{exp} \left( \min \left( 1 - \frac{\text{length of reference}}{\text{length of hypothesis}}, 0 \right) + \sum_{n=1}^{N} w_n \log p_n \right) $$ where $$ p_n $$ is the precision of n-grams and $$ w_n $$ is the weight for the n-gram order.

7. GAN Discriminator Loss#

- Description: In GANs like SeqGAN or TextGAN, the discriminator provides a loss signal that reflects how well the generator’s text resembles real text. The generator’s loss is typically the inverse of the discriminator’s success.

- Use Case: Used in GAN-based text generation models to refine the generator’s output to be more realistic.

- Formula: $$ \text{Generator Loss} = -\log(D(G(z))) $$ where $$ D(G(z)) $$ is the discriminator’s probability that the generated text $$ G(z) $$ is real.

Summary:#

Different loss functions serve different purposes in updating the parameters of text generation models. Cross-Entropy Loss and MLE Loss are standard for sequence modeling, while reinforcement learning-based losses and GAN discriminator losses are used for more advanced techniques like GANs and policy gradient methods. Each loss function is chosen based on the specific needs of the text generation task and the model architecture.

Can you explain with example how KL Divergence loss function works?#

When we say “measures the divergence between the predicted distribution and a target distribution,” we’re referring to how different or similar two probability distributions are from each other. Specifically, it’s about comparing the distribution of the model’s predictions (the predicted distribution) with the actual or expected distribution (the target distribution).

What is a Probability Distribution?#

A probability distribution assigns probabilities to different outcomes or events. For example, in the context of text generation, a probability distribution might tell us the likelihood of each word or token being the next in a sequence.

KL Divergence Explained:#

Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence is a measure of how one probability distribution diverges from a second, expected probability distribution. It’s not symmetric, meaning $$ (\text{KL}P | Q) $$ is not necessarily the same as $$ \text{KL}(Q | P) $$. The KL divergence is used to quantify how much information is lost when we use the predicted distribution instead of the target distribution.

Example:#

Let’s consider a simple example where we have a model that is predicting the next word in a sentence.

Scenario:#

Suppose we’re trying to predict the next word after “The cat is”. The target distribution might look like this based on real-world data:

- Target distribution $$ Q $$:

- “sleeping”: 0.7

- “running”: 0.2

- “eating”: 0.1

This distribution reflects the true probabilities of each word occurring next based on our training data.

Now, suppose our model predicts the following distribution:

- Predicted distribution $$ P $$:

- “sleeping”: 0.5

- “running”: 0.3

- “eating”: 0.2

KL Divergence Calculation:#

The KL divergence between the target distribution $$ Q $$ and the predicted distribution $$ P $$ can be calculated as:

$$ \text{KL}(Q | P) = \sum_{i} Q(i) \log \frac{Q(i)}{P(i)} $$

For our example:

$$ \text{KL}(Q | P) = (0.7) \log \frac{0.7}{0.5} + (0.2) \log \frac{0.2}{0.3} + (0.1) \log \frac{0.1}{0.2} $$

Let’s compute this step by step:

For “sleeping”:

$$ 0.7 \log \frac{0.7}{0.5} = 0.7 \times \log(1.4) \approx 0.7 \times 0.3365 = 0.2356 $$

For “running”:

$$ 0.2 \log \frac{0.2}{0.3} = 0.2 \times \log(0.6667) \approx 0.2 \times (-0.1761) = -0.0352 $$

For “eating”: $$ 0.1 \log \frac{0.1}{0.2} = 0.1 \times \log(0.5) \approx 0.1 \times (-0.3010) = -0.0301 $$

Finally, summing these values gives us:

$$ \text{KL}(Q | P) = 0.2356 - 0.0352 - 0.0301 = 0.1703 $$

Interpretation:#

- KL Divergence Value: The KL divergence value of 0.1703 indicates that there’s some divergence between the predicted and target distributions. If the predicted distribution $$ P $$ were exactly the same as the target distribution $$ Q $$, the KL divergence would be 0, indicating no divergence.

- Minimizing KL Divergence: In practice, during training, we try to minimize the KL divergence to make the model’s predictions as close as possible to the target distribution.

Summary:#

KL Divergence measures how much the predicted probability distribution diverges from the actual, expected distribution. In the context of our example, it quantifies how different the model’s predicted probabilities for the next word in a sentence are from the true probabilities based on training data. Minimizing KL divergence during training helps improve the model’s accuracy in making predictions.

What is Optimizer?#

Optimizers play a crucial role in deep neural network training. They are responsible for updating the model’s parameters in order to minimise the loss function, and ultimately improve the performance of the model. There are many different optimisers available, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, and choosing the right optimiser can make a significant impact on the training process.

What are the various optimization algorithms?#

Some popular optimisers include stochastic gradient descent (SGD), momentum, Adagrad, Adadelta, RProp, RMSprop, Adam, AMSGrad, and Nadam. These optimisers differ in how they calculate the updates to the model’s parameters, with some taking into account the historical gradient information, others using momentum to smooth out updates, and others adapting the learning rate based on the magnitude of the gradients. It’s important to carefully consider the properties of the cost function and the structure of the model when selecting an optimiser, as this can have a significant impact on the speed and stability of the training process.

Can you explain with example how these optimizers update the model parameters?#

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) - It updates the model parameters by taking the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters and subtracting it from the parameters.

$$\theta = \theta - \alpha \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$where $$\theta$$ is the model parameter, $$\alpha$$ is the learning rate, and $$J(\theta)$$ is the cost function.

Momentum - It accumulates the gradient of the previous steps to avoid oscillation and converge faster.

$v = \beta v - \alpha \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$$\theta = \theta + v$$

where $v$ is the velocity term, $$\beta$$ is the momentum hyperparameter.

Nesterov Accelerated Gradient (NAG) - It is an improved version of Momentum that takes into account the future position of the parameters based on the estimated gradient.

$v = \beta v - \alpha \frac{\partial J(\theta + \beta v)}{\partial \theta}$$$\theta = \theta + v$$

Adagrad - It adapts the learning rate to the parameters, performing larger updates for infrequent parameters and smaller updates for frequent parameters.

$$G = G + \left(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)^2$$$$\theta = \theta - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{G + \epsilon}} \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$

where $$G$$ is the sum of squares of past gradients, and $$\epsilon$$ is a small value to prevent division by zero.

Adadelta - It is an extension of Adagrad that reduces its aggressive, monotonically decreasing learning rate. $E[g^2]t = \gamma E[g^2]{t-1} + (1 - \gamma)\left(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)^2$

$$\Delta \theta_t = -\frac{\sqrt{E[\Delta \theta^2]_{t-1} + \epsilon}}{\sqrt{E[g^2]_t + \epsilon}} \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$

$$\theta = \theta + \Delta \theta_t$$

where $E[g^2]$ and $E[\Delta \theta^2]$ are the moving average of the square of gradients and the square of parameter updates, respectively, and $$\gamma$$ is the decay rate.

RProp - It uses the sign of the gradient to determine the direction of the update, with a dynamically adjusted step size for each parameter.

$$\Delta \theta_i = \text{sign}(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_i})\Delta \theta_{i,prev}$$

$$\theta_i = \theta_i - \Delta \theta_i$$

where $$\theta_i$$ is the current value of a model parameter, $$\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_i}$$ is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameter, $$\Delta \theta_{i,prev}$$ is the previous update to the parameter, and $$\text{sign}(\cdot)$$ is the sign function. The step size $$\Delta \theta_i$$ is determined dynamically based on the magnitude of the gradient.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) - It combines the advantages of Momentum and Adagrad, by considering both the average and the variance of the gradient for parameter updates.

$$m = \beta_1 m + (1 - \beta_1) \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$$$v = \beta_2 v + (1 - \beta_2) \left(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)^2$$

$$\hat{m} = \frac{m}{1 - \beta_1^t}$$

$$\hat{v} = \frac{v}{1 - \beta_2^t}$$

$$\theta = \theta - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{\hat{v}} + \epsilon} \hat{m}$$

where $$m$$ and $$v$$ are the first and second moment estimates, respectively, $$\beta_1$$ and $$\beta_2$$ are hyperparameters, and the rest of the terms are as defined above.

AMSGrad - It is an extension of Adam that ensures the learning rate does not get too small, even if the gradient is small.

$m = \beta_1 m + (1 - \beta_1) \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$$v = \max(\beta_2 v + (1 - \beta_2) \left(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)^2, v_{t-1})$$

$$\hat{m} = \frac{m}{1 - \beta_1^t}$$

$$\hat{v} = \frac{v}{1 - \beta_2^t}$$

$$\theta = \theta - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{\hat{v}} + \epsilon} \hat{m}$$

Nadam (Nesterov-Accelerated Adaptive Moment Estimation) - It combines NAG and Adam to take advantage of the rapid convergence of NAG and the adaptive learning rate of Adam.

$$m = \beta_1 m + (1 - \beta_1) \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}$$$$v = \beta_2 v + (1 - \beta_2) \left(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)^2$$

$$\hat{m} = \frac{m}{1 - \beta_1^t}$$

$$\hat{v} = \frac{v}{1 - \beta_2^t}$$

$$\theta = \theta - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{\hat{v}} + \epsilon} \left(\beta_1 \hat{m} + (1 - \beta_1) \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta}\right)$$

Author

Dr Hari Thapliyal

https://linkedin.com/in/harithapliyal

https://dasarpai.com

Comments: