Transformers Demystified A Step-by-Step Guide#

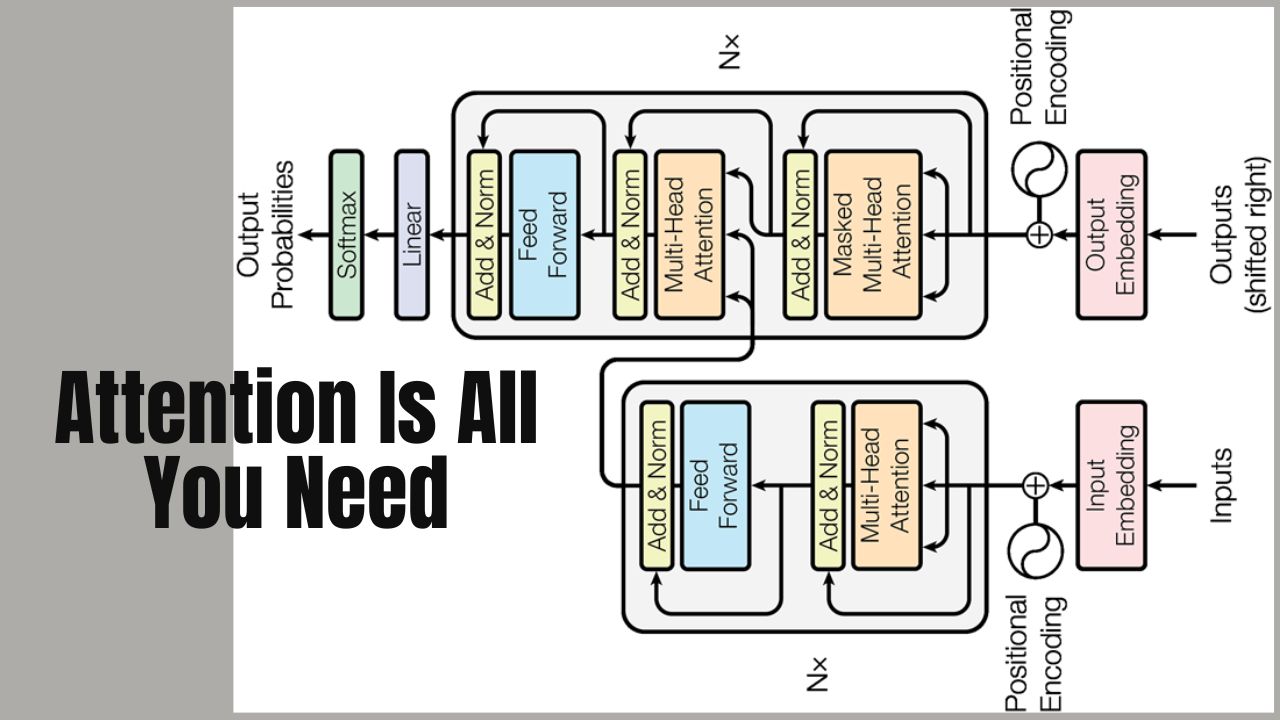

All modern Transformers are based on a paper “Attention is all you need”

Introduction#

This was the mother paper of all the transformer architectures we see today around NLP, Multimodal, Deep Learning. It was presented by Ashish Vaswani et al from Deep Learning / Google in 2017. We will discuss following and anything whatever question/observation/idea I have.

- The need Why this paper was needed? What problem it solved?

- What is transformer? What is encoder transformer? What is decoder transformer? What is encoder-decoder transformer?

- What is embedding? What is need for embedding? What are different types of embedding? What embeddingg is proposed in this work

- What benchmark dataset was used, what metrics were used and what was the performance of this model?

- Finally we will looks all the calculations with one illustration.

Encourage all to read this original paper.

What was need of this work?#

This paper addressed several limitations of previous sequence-to-sequence models used for tasks such as machine translation, text summarization, and other natural language processing (NLP) applications. The need for this paper arose from various challenges and limitations in existing models:

Limitations of Previous Models#

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks:

- Sequential Computation: RNNs and LSTMs process sequences step-by-step, which makes it difficult to parallelize computations and slows down training and inference.

- Long-Range Dependencies: RNNs and LSTMs struggle to capture dependencies in long sequences, leading to difficulties in understanding context over long distances.

- Gradient Issues: These models can suffer from vanishing or exploding gradient problems, particularly with long sequences.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs):

- Fixed Context Size: CNNs have a fixed receptive field, which can limit their ability to capture long-range dependencies effectively.

- Complexity: Extending CNNs to capture longer contexts can significantly increase the model’s complexity and computational cost.

The introduction of the Transformer architecture had a profound impact on the field of NLP and beyond. It paved the way for the development of large-scale pre-trained language models like BERT, GPT, and others, which have since become the foundation for many state-of-the-art AI applications. The principles of the Transformer architecture have also been adapted for other domains, such as image processing and reinforcement learning.

NLP Tasks#

Text Classification:

- Spam Detection: Classifying messages as spam or non-spam.

- Topic Classification: Categorizing text into predefined topics or categories.

- Sarcasm Detection

- Offensive Language Detection

Sentiment and Emotion Analysis: Determining the sentiment or emotional tone expressed in a text.

Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifying and classifying named entities (e.g., people, organizations, locations) within a text.

Part-of-Speech Tagging (POS Tagging): Assigning parts of speech (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives) to each word in a text.

Machine Translation: Translating text from one language to another (e.g., English to French).

Language Modeling: Predicting the next word or character in a sequence, often used in generating text or improving other NLP tasks.

Text Summarization:

- Extractive Summarization: Extracting key sentences from a text to create a summary.

- Abstractive Summarization: Generating a concise summary that captures the main ideas of the text.

Question Answering: Providing answers to questions based on a given text or dataset.

Text Generation: Generating coherent and contextually relevant text, such as in chatbots or story generation.

Text Similarity: Measuring how similar two pieces of text are, which can be used in tasks like duplicate detection or paraphrase identification.

Coreference Resolution: Identifying when different expressions in a text refer to the same entity.

Speech Recognition: Converting spoken language into text.

Speech Synthesis (Text-to-Speech): Converting text into spoken language.

Dialogue Systems:

- Chatbots: Engaging in conversation with users.

- Virtual Assistants: Assisting users with tasks through natural language interactions.

Information Retrieval: Finding relevant information within large datasets or the web, such as search engines.

Dependency Parsing: Analyzing the grammatical structure of a sentence to establish relationships between words.

Grammar and Spelling Correction: Identifying and correcting grammatical errors and typos in text.

Textual Entailment: Determining if one sentence logically follows from another.

Word Sense Disambiguation: Identifying which sense of a word is used in a given context.

Natural Language Inference (NLI): Determining if a premise logically entails a hypothesis.

Each of these tasks involves different techniques and models, often leveraging machine learning and deep learning to achieve state-of-the-art performance.

Background#

Google Translate was launched on April 28, 2006. Initially, it was a statistical machine translation service that used United Nations and European Parliament transcripts to gather linguistic data.

It used a statistical machine translation (SMT) approach. This method relied on statistical models to translate text based on patterns found in large volumes of bilingual text corpora. The SMT system analyzed these patterns to make educated guesses about the most likely translations.

In 2016, Google Translate transitioned to using a neural machine translation (NMT) system, specifically the Google Neural Machine Translation (GNMT) system. This system uses deep learning techniques and neural networks to provide more accurate and natural translations by considering the entire sentence as a whole, rather than translating piece by piece.

Metrics#

BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) score, which measures the quality of machine-translated text against reference translations.

Google reported that the new NMT system achieved improvements ranging from 55% to 85% across various language pairs in terms of BLEU scores compared to their previous SMT system. This was a substantial leap in translation quality.

- For Chinese to English translations, the BLEU score improvement was reported to be around 24.2, a significant increase from the previous SMT system.

- For English to French, the BLEU score improvement was noted as being around 5-8 points higher than the SMT system.

Benchmarks#

WMT 2014 English-to-German (En-De) Translation Task:

- Dataset: The dataset consisted of 4.5 million sentence pairs.

- Performance: The Transformer model achieved a BLEU score of 28.4, which was a significant improvement over the previous state-of-the-art models.

WMT 2014 English-to-French (En-Fr) Translation Task:

- Dataset: The dataset consisted of 36 million sentence pairs.

- Performance: The Transformer model achieved a BLEU score of 41.8, which also outperformed previous models.

Key terms#

Transformer Architecture: The paper introduces the Transformer, a novel architecture solely based on attention mechanisms, dispensing with recurrence and convolutions entirely.

Attention Mechanism: The core idea is the use of self-attention, allowing the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence when forming a representation of each word.

Self-Attention: Self-attention allows each word to focus on different parts of the input sentence, making it easier for the model to understand context and relationships between words.

Multi-Head Attention: Instead of performing a single attention function, the Transformer employs multiple attention heads, each focusing on different parts of the sentence, capturing diverse aspects of the information.

Positional Encoding: Since the Transformer does not have recurrence, it uses positional encodings to give the model information about the position of each word in the sentence.

Layer Normalization and Residual Connections: Each sub-layer (multi-head attention and feed-forward) is followed by layer normalization and residual connections, aiding in training deep networks.

Encoder-Decoder Structure: The Transformer is composed of an encoder (which processes the input) and a decoder (which generates the output). Each consists of multiple layers of self-attention and feed-forward networks.

Performance: The Transformer achieves state-of-the-art performance on several NLP tasks while being more parallelizable and faster to train than recurrent architectures like LSTMs and GRUs.

Scalability: Due to its architecture, the Transformer scales well with the amount of available data and computational power, making it suitable for large-scale tasks.

With “Encoder Only” Architecture we can do.#

An encoder-only architecture, such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), is typically used for tasks that require understanding and representing input sequences without generating sequences. Here are some common NLP tasks that can be effectively handled using an encoder-only architecture:

Text Classification:

- Sentiment Analysis: Determining the sentiment (positive, negative, neutral) expressed in a piece of text.

- Spam Detection: Classifying messages as spam or not spam.

- Topic Classification: Categorizing text into predefined topics or categories.

Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifying and classifying named entities (e.g., persons, organizations, locations) within the text.

Part-of-Speech Tagging (POS Tagging): Assigning parts of speech (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives) to each word in the text.

Question Answering (Extractive): Extracting an answer from a given context based on a query. For instance, answering questions from a passage of text.

Textual Entailment: Determining whether a given hypothesis logically follows from a premise (also known as Natural Language Inference, NLI).

Sentence Pair Classification:

- Paraphrase Detection: Identifying whether two sentences are paraphrases of each other.

- Semantic Similarity: Measuring how similar two sentences or phrases are in meaning.

Coreference Resolution: Determining which expressions in a text refer to the same entity.

Text Summarization (Extractive): Selecting the most important sentences from a document to create a summary.

Grammar and Spelling Correction: Identifying and correcting grammatical errors and typos in text.

Information Retrieval: Ranking and retrieving relevant documents based on a query.

Document Classification: Categorizing entire documents into classes or categories.

Named Entity Disambiguation: Resolving ambiguities in named entities to identify the correct entity among potential candidates.

Feature Extraction for Downstream Tasks: Generating contextualized embeddings from text to be used as features in other machine learning models.

Encoder-only models are particularly effective in tasks that benefit from understanding the context and semantics of the input text, as they are designed to capture rich, contextual representations of the input data.

With “Decoder only” Architecture we can do.#

Decoder-only architectures, such as GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), are primarily designed for tasks involving text generation. These models are well-suited for autoregressive tasks where the goal is to predict or generate text based on a given context. Here are some common NLP tasks that can be effectively handled using a decoder-only architecture:

Text Generation:

- Creative Writing: Generating coherent and contextually relevant creative content, such as stories, poems, or dialogues.

- Content Generation: Creating blog posts, articles, or other types of written content.

Language Modeling:

- Next Word Prediction: Predicting the next word or token in a sequence given the preceding context.

- Completion: Providing completion for a partially written sentence or text.

Conversational AI:

- Chatbots: Engaging in conversation with users, generating responses to user inputs.

- Virtual Assistants: Assisting with tasks through natural language interactions.

Text Summarization (Abstractive): Generating a concise summary of a text that captures the main ideas, potentially rephrasing and reorganizing information.

Machine Translation: Translating text from one language to another in an autoregressive manner, generating translated sentences token by token.

Dialogue Generation:

- Interactive Fiction: Generating dialogues in interactive fiction or role-playing scenarios.

- Conversational Agents: Generating responses in a conversation based on the context of the dialogue.

Storytelling: Creating narratives or expanding on a given prompt to generate a complete story or narrative.

Autoregressive Text Editing: Modifying or editing text based on a given context, such as rewriting or expanding text.

Text-based Games: Generating responses and interactions in text-based games or interactive storytelling environments.

Decoder-only architectures excel in generating text sequences and modeling complex language patterns due to their autoregressive nature. They predict the next token in a sequence based on the previous tokens, which makes them ideal for tasks that involve creating or completing text.

With Encoder-Decoder Architecture we can do following task.#

Encoder-decoder architectures, like those used in the original Transformer model and its derivatives (e.g., T5, BART), are particularly well-suited for tasks that involve transforming one sequence into another. These models leverage the encoder to process and understand the input sequence and the decoder to generate the output sequence. Here are some key tasks that benefit from an encoder-decoder architecture:

Machine Translation: Translating text from one language to another. The encoder processes the source language text, while the decoder generates the translated text in the target language.

Text Summarization:

- Abstractive Summarization: Generating a concise and coherent summary of a document, potentially rephrasing and synthesizing information from the source text.

Text-to-Text Tasks: Treating various NLP tasks as text-to-text problems, where both the input and output are sequences of text. Examples include:

- Question Answering: Generating answers to questions based on a provided context or passage.

- Text Generation with Constraints: Generating text based on specific constraints or instructions.

Image Captioning: Generating a textual description of an image. The encoder processes features extracted from the image, and the decoder generates a descriptive sentence.

Speech-to-Text: Converting spoken language (speech) into written text. The encoder processes the audio features, while the decoder generates the corresponding text.

Text-Based Conversational Systems:

- Dialogue Generation: Generating responses in a conversation where the input may be a previous dialogue context or user query, and the output is a coherent response.

Paraphrase Generation: Rewriting or generating paraphrased versions of a given text while preserving its meaning.

Story Generation: Generating complete stories or narratives based on a prompt or initial context.

Semantic Parsing: Converting natural language into a structured format or query (e.g., converting a sentence into a SQL query).

Text Style Transfer: Transforming the style of a given text while preserving its original meaning (e.g., changing a formal text into an informal one).

Multi-Modal Tasks: Combining multiple types of input (e.g., text and images) to generate output in one modality (e.g., generating text from images or audio).

Encoder-decoder architectures are versatile and powerful for tasks that require generating output sequences based on complex input sequences, making them suitable for a wide range of applications in natural language processing and beyond.

Why do we need encoder-decoder architectures?#

Both encoder-only and decoder-only architectures have their own strengths and are suited to different types of tasks. The choice between them often depends on the specific requirements of the task and the trade-offs in terms of computational resources, complexity, and performance. Here’s a comparison of why you might choose an encoder-decoder architecture over a decoder-only one, and considerations about resource usage:

Handling Complex Input-Output Relationships:

- Task Complexity: Encoder-decoder models excel at tasks where the input and output are significantly different in structure or length, such as machine translation or summarization. The encoder captures the complex relationships in the input sequence, and the decoder generates a well-formed output sequence.

- Contextual Encoding: The encoder can effectively represent the entire input sequence in a structured way, allowing the decoder to generate a sequence that reflects the input’s context accurately.

Improved Performance on Sequence-to-Sequence Tasks:

- Attention Mechanism: The encoder-decoder framework allows for sophisticated attention mechanisms that can focus on different parts of the input sequence while generating the output. This is crucial for tasks where the output needs to reference specific parts of the input.

Versatility:

- Generalization: Encoder-decoder models can be adapted for a variety of tasks beyond just sequence generation, including text-to-text transformations and multi-modal tasks (e.g., generating text from images).

Decoupling of Representation and Generation:

- Modularity: The separation of encoding and decoding processes allows for specialized models and training procedures. This can be advantageous when tuning models for specific tasks.

Resource Considerations#

Computational Resources:

- Encoder-Decoder Models: Typically require more resources compared to decoder-only models because they need to handle both encoding and decoding processes. This involves more parameters and more complex computations, particularly for tasks with long input sequences.

- Decoder-Only Models: Can be more resource-efficient for tasks that involve generating text based on a fixed context, as they focus solely on the generation process.

Training and Inference:

- Encoder-Decoder Models: Training can be more resource-intensive due to the dual structure (encoder and decoder). Inference can also be slower because it involves both encoding the input and generating the output.

- Decoder-Only Models: Training might be less complex since there is only one component involved, and inference can be faster for generation tasks due to the lack of a separate encoding step.

Summary#

- Encoder-Decoder Models: Best suited for tasks where the input and output sequences are complex and need sophisticated handling. They provide a structured approach to managing different sequence transformations and can handle a wide range of sequence-to-sequence tasks.

- Decoder-Only Models: More efficient for tasks focused solely on text generation or autoregressive modeling, where the context is provided, and the focus is on generating a continuation or response.

Choosing between encoder-decoder and decoder-only architectures depends on the specific task requirements and the trade-offs between performance and computational efficiency. For tasks involving intricate input-output relationships, an encoder-decoder model is often preferred despite the higher resource demands. For tasks centered on generating sequences based on a fixed context, a decoder-only model may be more resource-efficient.

Popular Transformer Architectures#

Transformer architecture has evolved significantly since the original “Attention Is All You Need” paper. Here are some notable variations and advancements:

Original Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017):

- Structure: Comprises an encoder-decoder architecture with self-attention and multi-head attention mechanisms.

- Use Case: Initially designed for machine translation.

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers):

- Structure: Uses only the encoder part of the Transformer.

- Training: Pre-trained using a masked language model (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP) objectives.

- Use Case: Effective for various NLP tasks like question answering, sentiment analysis, and named entity recognition.

GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer):

- Structure: Uses only the decoder part of the Transformer.

- Training: Pre-trained using a unidirectional (left-to-right) language model objective.

- Variants: GPT-2 and GPT-3, with GPT-4 being the latest, have scaled up the number of parameters and improved performance significantly.

- Use Case: Text generation, language translation, and more.

T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer):

- Structure: Converts all NLP tasks into a text-to-text format.

- Training: Pre-trained on a diverse mixture of tasks and fine-tuned for specific tasks.

- Use Case: Versatile across different NLP tasks.

RoBERTa (A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach):

- Structure: An optimized version of BERT with more training data and longer training times.

- Use Case: Improved performance on various NLP benchmarks compared to BERT.

ALBERT (A Lite BERT):

- Structure: Reduces the number of parameters using factorized embedding parameterization and cross-layer parameter sharing.

- Use Case: Efficient and lightweight version of BERT for various NLP tasks.

DistilBERT:

- Structure: A smaller, faster, and cheaper version of BERT.

- Training: Uses knowledge distillation during pre-training.

- Use Case: Suitable for environments with limited computational resources.

XLNet:

- Structure: Integrates autoregressive and autoencoding approaches.

- Training: Uses permutation-based training to capture bidirectional context.

- Use Case: Effective for language modeling and various downstream NLP tasks.

Transformer-XL:

- Structure: Introduces a segment-level recurrence mechanism.

- Training: Handles long-term dependencies better than traditional Transformers.

- Use Case: Suitable for tasks requiring long context understanding, like document modeling.

Vision Transformer (ViT):

- Structure: Applies Transformer architecture to image classification tasks.

- Training: Treats image patches as tokens and processes them similarly to text.

- Use Case: Effective for various computer vision tasks.

DeBERTa (Decoding-enhanced BERT with disentangled attention):

- Structure: Enhances BERT with disentangled attention and improved position embeddings.

- Use Case: Achieves state-of-the-art results on various NLP benchmarks.

Swin Transformer:

- Structure: Applies hierarchical vision Transformer architecture with shifted windows.

- Training: Designed for image classification and dense prediction tasks.

- Use Case: Effective for object detection, semantic segmentation, and more.

These variations demonstrate the versatility and adaptability of Transformer architectures across a wide range of applications in both natural language processing and computer vision.

Why Multi headed attention?#

The multi-head attention mechanism in Transformers enables the model to focus on different aspects of the input data simultaneously. Here are examples of various aspects that attention mechanisms can capture:

Syntactic Relationships:#

Example: In the sentence “The cat sat on the mat,” different heads might focus on different parts of speech relationships, such as subject-verb (“cat” and “sat”) and preposition-object (“on” and “mat”).

Semantic Relationships:#

Example: In the sentence “He played the piano beautifully,” one head might focus on the verb “played” and its direct object “piano,” while another head focuses on the adverb “beautifully” modifying “played.”

Coreference Resolution:#

Example: In the text “Alice went to the market. She bought apples,” one head might track the coreference between “Alice” and “She.”

Long-Range Dependencies:#

Example: In the sentence “The book that you recommended to me last week was fascinating,” one head might focus on the relationship between “book” and “fascinating,” which are far apart in the sentence.

Positional Information:#

Example: Different heads can capture relative positional information, such as the beginning, middle, and end of a sentence, which is crucial for understanding the structure.

Named Entity Recognition:#

Example: In the sentence “Barack Obama was born in Hawaii,” one head might focus on identifying “Barack Obama” as a person.

Polarity and Sentiment:#

- Could capture positive or negative sentiment associated with different parts of the text.

- May focus on identifying subjective vs. objective statements. Ho

How attention works?#

The input embedding is linearly projected into three different spaces to generate queries (𝑄), keys (𝐾), and values (𝑉).

$${Attention}(Q, K, V) = {softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V$$

Where:

- Q is the query matrix.

- K is the key matrix.

- V is the value matrix.

- $d_k$ is the dimension of the keys.

How multihead attention works.#

- Base model has 512 dim embedding vector, large model has 1024 dim embedding vector.

- Position vector of the same size is used.

- Both vectors are pair wise added.

- Base model has 8 heads and large model has 16 heads. Thus each head has 512/8 or 1024/16 i.e. 64 dim vector.

How Q, K, V Calculated?#

Input Embedding Dimension for Base Model: 512

Number of Heads: 8

Dimension per Head: Each head will handle $$\frac{512}{8} = 64$$ dimensions.

Steps for Multi-Head Attention:#

Linear Projections:

- The input embedding (of dimension 512) is linearly projected into three different spaces to generate queries ($$Q$$), keys ($K$), and values ($V$).

- Each projection is typically done using separate learned weight matrices.

- These projections result in three vectors: $Q$, $K$, and $V$, each of dimension 512.

- Example: Linear Projections:

- For the input $X$ of shape $$[ batch_size, sequence_length, 512 ]$:

- $Q = XW_Q$, where $W_Q$ is a weight matrix of shape $[512, 512]$.

- $K = XW_K$, where $W_K$ is a weight matrix of shape $[512, 512]$.

- $V = XW_V$, where $W_V$ is a weight matrix of shape $[512, 512]$.

Splitting into Heads:

- After the projection, the $$Q$$, $$K$$, and $$V$$ vectors are split into 8 parts (heads).

- Each part will have $$ \frac{512}{8} = 64 $$ dimensions.

- This means each head gets a 64-dimensional sub-vector from $$Q$$, $$K$$, and $$V$$.

- Example: Splitting into Heads:

- Each of the $$Q$$, $$K$$, and $$V$$ matrices (of shape $$ {batch_size}, {sequence_length}, 512 $$ is reshaped and split into 8 heads.

- For each matrix, this reshaping results in shape $$ batch_size, sequence_length, 8, 64 $$.

- The 8 heads mean we now have 8 sets of $$Q$$, $$K$$, and $$V$$ vectors, each of dimension 64.

Scaled Dot-Product Attention (Per Head):#

Each of the 8 heads performs scaled dot-product attention independently: $$ {Attention}(Q_i, K_i, V_i) = {softmax}\left(\frac{Q_i K_i^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V_i $$ where $$ d_k = 64 $$ is the dimension of each head.

Concatenation and Final Linear Layer:#

The outputs from all 8 heads are concatenated:

- Concatenated output shape: $$batch_size, sequence_length, 8 \times 64 = batch_size, sequence_length, 512$$ .

This concatenated vector is then passed through a final linear layer (with weight matrix of shape $$[512, 512]$$) to produce the final output of the multi-head attention mechanism.

This process ensures that each head independently attends to different parts of the input, capturing diverse aspects of the data.

Floating Point Value Range#

These embedding vectors holds floating point numbers. These numbers may be 64bit, 32bit, 16bit, 8bit, 4bit. What will be the range of value if we use these different bit size to hold floating number. This is useful when you are doing quantization.

Embedding vectors in many deep learning frameworks typically use IEEE 754 double-precision floating-point format (64-bit) for representing values, but there are also other precision formats used depending on the specific requirements and hardware capabilities.

Apart from number of parameters these floating point precision also make model bulky. To reduce the model size we reduce these floating point precision. This process is called quantization. For edge devices or making model run on low graded machine we can choose quantization of the model to 4bit or 8bit floating points, off course we suffer the quality of output due to this.

Common Precision Formats for Embeddings#

Double Precision (64-bit):

- Format: IEEE 754 double-precision floating-point.

- Precision: Provides about 15-17 significant decimal digits of precision.

- Range: Can represent values from approximately $$ \pm 5 \times 10^{-324} $$ to $$ \pm 1.79 \times 10^{308} $$.

- Use Case: Often used when high precision is required, but it’s less common in practice for embeddings due to the increased computational and memory overhead.

Single Precision (32-bit):

- Format: IEEE 754 single-precision floating-point.

- Precision: Provides about 6-9 significant decimal digits of precision.

- Range: Can represent values from approximately $$ \pm 1.18 \times 10^{-38} $$ to $$ \pm 3.4 \times 10^{38} $$.

- Use Case: More common for embeddings due to a good balance between precision and computational efficiency.

Half Precision (16-bit):

- Format: IEEE 754 half-precision floating-point.

- Precision: Provides about 3-4 significant decimal digits of precision.

- Range: Can represent values from approximately $$ \pm 6.1 \times 10^{-5} $$ to $$ \pm 6.5 \times 10^{4} $$.

- Use Case: Used to reduce memory usage and increase computational efficiency, especially during training with GPUs that support mixed precision.

BFloat16 (16-bit):

- Format: A variant of 16-bit floating-point with a different exponent and mantissa configuration, designed to be more efficient for certain computations.

- Precision: Similar to half precision but with a larger exponent range.

- Use Case: Used in some TensorFlow models and other frameworks to optimize performance while maintaining acceptable precision.

In Summary#

- IEEE 754 Double Precision is used when high precision is crucial, but it is less common for embeddings due to the larger memory footprint and computation requirements.

- IEEE 754 Single Precision is the most common format for embeddings in many deep learning applications due to its efficiency and sufficient precision.

- Half Precision and BFloat16 are used for further optimization, particularly in training scenarios where memory and computational efficiency are critical.

The choice of precision format depends on the trade-offs between precision, memory usage, and computational efficiency.

Illustration of Working of Transformer#

For the sake of simplicity, let’s walk through an example of how a ChatGPT-like architecture generates text, using an 8-dimensional word embedding, a vocabulary size of 100, and a multi-headed attention mechanism with 2 heads and 3 layers. We will also perform the computations for the self-attention using the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) matrices.

Step 1: Tokenization and Embedding#

Vocabulary: 100 unique tokens.

Input Sentence: “Hello world”

Token IDs:

- “Hello” might be token ID 42.

- “world” might be token ID 85.

Embedding: Each token ID is mapped to an 8-dimensional vector.

- Embedding for “Hello” (token ID 42): [0.1, -0.2, 0.3, 0.4, -0.5, 0.2, -0.1, 0.0]

- Embedding for “world” (token ID 85): [-0.3, 0.1, 0.2, -0.4, 0.5, -0.2, 0.3, -0.1]

We also need to compute position embedding. Refer Position Embedding Mechanism

Step 2: Input to the Transformer Model#

These embeddings are passed as input to the model.

Input Matrix:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & -0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 & -0.5 & 0.2 & -0.1 & 0.0 \ -0.3 & 0.1 & 0.2 & -0.4 & 0.5 & -0.2 & 0.3 & -0.1 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Step 3: Self Attention#

- Multi-Head Self-Attention

- Combining Multi-Head Attention

For Head 2, similar computations will be performed to obtain $$ Q_2 $$, $$ K_2 $$, $$ V_2 $$, and the attention output. The outputs from both heads will be concatenated and then projected back into the original embedding dimension using a weight matrix $$ W^O $$.

Step 4. Processing Through Transformer Layers#

The output of the multi-head attention layer will then pass through the feed-forward neural network (FFNN) and normalization layers, completing the processing for one layer of the transformer. This process is repeated for the remaining layers, in our example 3 layers.

- Feedforward Neural Networks

- Layer Normalization

- Residual Connections

Each layer refines the embeddings based on the input context.

Step 5. Output Logits#

After processing through the Transformer layers, we get output vectors (logits) for each token position.

Output Logits for the Next Token: Let’s assume our logits for the next token are a 100-dimensional vector (one value per token in the vocabulary). For simplicity:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 1.5, & -0.3, & \dots, & 0.8 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Step 6. Softmax Function#

The logits are converted to probabilities using the softmax function.

Softmax Output:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 0.1, & 0.05, & \dots, & 0.15 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Step 7. Token Selection#

A token is selected based on the probabilities. Using sampling, top-k, or greedy decoding:

- Let’s say token ID 75 is selected, corresponding to the token “everyone”.

Step 8. Generating the Next Token#

The process repeats. The input now includes the previous tokens “Hello world” and the new token “everyone”. The model generates the next token based on this updated context.

Generating Text#

To generate text, the model uses these layers iteratively, predicting the next token in the sequence based on the previously generated tokens and the context provided by the input sequence. The output is passed through a final linear layer and softmax to produce probabilities for the next token, from which the next token is sampled or chosen.

By repeating this process, the model generates text token by token until a specified end condition is met.

What different parameters are learned during transformer training?#

Transformer models like GPT3, GPT3.5, GPT4.0, Gemma, PaLM, Llama etc has billions of parameters. What are these parameters which are learned during training?

In large language models like ChatGPT, weights and biases are integral to the model’s operation, especially within the transformer architecture. Here’s a detailed breakdown of different weights and biases used in such models, including those related to attention mechanisms:

1. Weights and Biases in Transformer Architecture#

Attention Mechanism Weights#

Query Weights (W_q): These weights transform the input embeddings or hidden states into query vectors. In the attention mechanism, the query vector is compared against keys to compute attention scores.

Key Weights (W_k): These weights transform the input embeddings or hidden states into key vectors. The attention scores are computed by comparing these keys with the query vectors.

Value Weights (W_v): These weights transform the input embeddings or hidden states into value vectors. The output of the attention mechanism is a weighted sum of these value vectors, based on the attention scores.

Output Weights (W_o): After applying the attention mechanism, the output vectors are transformed by these weights before being passed to subsequent layers.

Feed-Forward Network Weights#

Weights (W_ff): The feed-forward network within each transformer block has its own set of weights for transforming the hidden states. This usually includes two sets of weights:

- Weight Matrices for Linear Transformations: These weights perform linear transformations in the feed-forward network, often involving two layers with an activation function (e.g., ReLU) in between.

Biases (b_ff): Biases are used along with the weights in the feed-forward network to adjust the activation values.

Layer Normalization Weights#

- Gamma (γ): Scaling parameter used in layer normalization to adjust the normalized output.

- Beta (β): Shifting parameter used in layer normalization to adjust the mean of the normalized output.

2. Overall Model Weights and Biases#

Embedding Weights#

- Token Embedding Weights: These weights map input tokens (words or subwords) to continuous vector representations (embeddings).

- Position Embedding Weights: These weights add positional information to the embeddings to encode the order of tokens in the sequence.

Layer Weights#

Weights in Each Transformer Layer: Each layer of the transformer model has its own set of weights and biases for both the attention mechanism and the feed-forward network.

Residual Connection Weights: Residual connections (or skip connections) within each transformer layer often involve weights for combining the input and output of the layer.

Summary#

In summary, the different weights and biases in a model like ChatGPT are:

Attention Mechanism:

- Query Weights (W_q)

- Key Weights (W_k)

- Value Weights (W_v)

- Output Weights (W_o)

Feed-Forward Network:

- Weights (W_ff)

- Biases (b_ff)

Layer Normalization:

- Gamma (γ)

- Beta (β)

Embedding Weights:

- Token Embedding Weights

- Position Embedding Weights

These weights and biases are learned during the training phase and are used during inference to generate responses based on the input data. Each component of the model contributes to its ability to understand and generate human-like text.

Self Attention Mechanism#

Compute Q, K, V Matrices for Multi-Head Attention (2 heads)#

We’ll compute Q, K, and V matrices for each head.

Weight Matrices for Q, K, V for Head 1:

$$ W^Q_1, W^K_1, W^V_1 \in \mathbb{R}^{8 \times 4} $$

Weight Matrices for Q, K, V for Head 2:

$$ W^Q_2, W^K_2, W^V_2 \in \mathbb{R}^{8 \times 4} $$

For simplicity, let’s use random matrices. In practice, these are learned during training.

Embeddings:

$$ X = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & -0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 & -0.5 & 0.2 & -0.1 & 0.0 \ -0.3 & 0.1 & 0.2 & -0.4 & 0.5 & -0.2 & 0.3 & -0.1 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Weight Matrices (randomly initialized for this example):

Head 1:

$$ W^Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^K_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^V_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Head 2:

$$ W^Q_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.2 & 0.1 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^K_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^V_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Compute Q, K, V for each token for each head:

Head 1:

$$ Q_1 = X \cdot W^Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & -0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 & -0.5 & 0.2 & -0.1 & 0.0 \ -0.3 & 0.1 & 0.2 & -0.4 & 0.5 & -0.2 & 0.3 & -0.1 \ \end{bmatrix} \cdot W^Q_1

K_1 = X \cdot W^K_1

V_1 = X \cdot W^V_1 $$

Head 2:

$$ Q_2 = X \cdot W^Q_2

K_2 = X \cdot W^K_2

V_2 = X \cdot W^V_2 $$

Let’s compute these step by step.

Compute Q, K, V for Head 1#

Input Embeddings:

$$ X = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & -0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 & -0.5 & 0.2 & -0.1 & 0.0 \ -0.3 & 0.1 & 0.2 & -0.4 & 0.5 & -0.2 & 0.3 & -0.1 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Weight Matrices for Head 1:

$$ W^Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^K_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.4 & 0.3 \ \end{bmatrix}

W^V_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ 0.3 & 0.4 & 0.1 & 0.2 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Compute Q, K, V for each token for Head 1:#

$$ Q_1 = X \cdot W^Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & -0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 & -0.5 & 0.2 & -0.1 & 0.0 \ -0.3 & 0.1 & 0.2 & -0.4 & 0.5 & -0.2 & 0.3 & -0.1 \ \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.3 & 0.4 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Performing the matrix multiplication:

$$ Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} (0.1 \times 0.1) + (-0.2 \times 0.1) + (0.3 \times 0.1) + (0.4 \times 0.1) + (-0.5 \times 0.1) + (0.2 \times 0.1) + (-0.1 \times 0.1) + (0 \times 0.1) & \dots & \ (-0.3 \times 0.1) + (0.1 \times 0.1) + (0.2 \times 0.1) + (-0.4 \times 0.1) + (0.5 \times 0.1) + (-0.2 \times 0.1) + (0.3 \times 0.1) + (-0.1 \times 0.1) & \dots & \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Simplifying:

$$ Q_1 = \begin{bmatrix} -0.01 & -0.02 & -0.03 & -0.04 \ 0.02 & 0.04 & 0.06 & 0.08 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Following the same steps for $$ K_1 $$ and $$ V_1 $$:

$$ K_1 = X \cdot W^K_1

= \begin{bmatrix} 0.15 & 0.30 & 0.45 & 0.60 \ 0.10 & 0.20 & 0.30 & 0.40 \ \end{bmatrix}

V_1 = X \cdot W^V_1

= \begin{bmatrix} 0.28 & 0.56 & 0.84 & 1.12 \ 0.24 & 0.48 & 0.72 & 0.96 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Similarly you compute for head 2. Finally you concatenate both vectors and get 2x8 size matrix (same size which was input for the self attention)

Step 3: Self-Attention Calculation#

Compute attention scores:#

$$ \text{Scores} = Q_1 \cdot K_1^T = \begin{bmatrix} -0.01 & -0.02 & -0.03 & -0.04 \ 0.02 & 0.04 & 0.06 & 0.08 \ \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 0.15 & 0.10 \ 0.30 & 0.20 \ 0.45 & 0.30 \ 0.60 & 0.40 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Performing the matrix multiplication:

$$ \text{Scores} = \begin{bmatrix} -0.01 \times 0.15 + -0.02 \times 0.30 + -0.03 \times 0.45 + -0.04 \times 0.60 & -0.01 \times 0.10 + -0.02 \times 0.20 + -0.03 \times 0.30 + -0.04 \times 0.40 \ 0.02 \times 0.15 + 0.04 \times 0.30 + 0.06 \times 0.45 + 0.08 \times 0.60 & 0.02 \times 0.10 + 0.04 \times 0.20 + 0.06 \times 0.30 + 0.08 \times 0.40 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Simplifying:

$$ \text{Scores} = \begin{bmatrix} -0.015 - 0.006 - 0.0135 - 0.024 & -0.01 - 0.004 - 0.009 - 0.016 \ 0.03 + 0.012 + 0.027 + 0.048 & 0.02 + 0.008 + 0.018 + 0.032 \ \end{bmatrix}

\text{Scores} = \begin{bmatrix} -0.0585 & -0.039 \ 0.117 & 0.078 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Apply softmax to obtain attention weights:#

$$ \text{Attention Weights} = \text{softmax}(\text{Scores})

\text{Attention Weights} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{e^{-0.0585}}{e^{-0.0585} + e^{-0.039}} & \frac{e^{-0.039}}{e^{-0.0585} + e^{-0.039}} \ \frac{e^{0.117}}{e^{0.117} + e^{0.078}} & \frac{e^{0.078}}{e^{0.117} + e^{0.078}} \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Simplifying:

$$ \text{Attention Weights} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{1 + e^{0.0195}} & \frac{e^{0.0195}}{1 + e^{0.0195}} \ \frac{1}{1 + e^{-0.039}} & \frac{e^{-0.039}}{1 + e^{-0.039}} \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Approximating the values:

$$ \text{Attention Weights} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.495 & 0.505 \ 0.510 & 0.490 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Compute the weighted sum of the values:#

$$ \text{Output} = \text{Attention Weights} \cdot V_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0.495 & 0.505 \ 0.510 & 0.490 \ \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 0.28 & 0.56 & 0.84 & 1.12 \ 0.24 & 0.48 & 0.72 & 0.96 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Performing the matrix multiplication:

$$ \text{Output} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.495 \times 0.28 + 0.505 \times 0.24 & 0.495 \times 0.56 + 0.505 \times 0.48 & 0.495 \times 0.84 + 0.505 \times 0.72 & 0.495 \times 1.12 + 0.505 \times 0.96 \ 0.510 \times 0.28 + 0.490 \times 0.24 & 0.510 \times 0.56 + 0.490 \times 0.48 & 0.510 \times 0.84 + 0.490 \times 0.72 & 0.510 \times 1.12 + 0.490 \times 0.96 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Simplifying:

$$ \text{Output} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.1386 + 0.1212 & 0.2772 + 0.2424 & 0.4158 + 0.3636 & 0.5544 + 0.4848 \ 0.1428 + 0.1176 & 0.2856 + 0.2304 & 0.4284 + 0.3432 & 0.5712 + 0.456 \ \end{bmatrix}

\text{Output} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2598 & 0.5196 & 0.7794 & 1.0392 \ 0.2604 & 0.516 & 0.7716 & 1.0272 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

Position Embedding Mechanism#

Position embeddings are used in transformers to provide information about the order of tokens in a sequence. The most common method for computing position embeddings is using sine and cosine functions of different frequencies. This method was introduced in the original transformer paper “Attention Is All You Need”. The formulas for the position embeddings are as follows:

Formulas for Position Embedding#

For a given position $$ pos $$ and embedding dimension $$ i $$:

- Sine Function for Even Indices:

$$ PE(pos, 2i) = \sin\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{\frac{2i}{d_{\text{model}}}}}\right) $$

- Cosine Function for Odd Indices:

$$ PE(pos, 2i+1) = \cos\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{\frac{2i}{d_{\text{model}}}}}\right) $$

Where:

- pos is the position of the token in the sequence (starting from 0).

- i is the dimension index (also starting from 0).

- $$d_{\text{model}}$$ is the dimensionality of the embeddings.

Explanation#

- Even Index: For even values of i, the position embedding is computed using the sine function.

- Odd Index: For odd values of i, the position embedding is computed using the cosine function.

- Frequency: The denominator $$10000^{\frac{2i}{d_{\text{model}}}}$$ ensures that different dimensions have different frequencies. The values for sine and cosine vary more slowly for larger dimensions, capturing different levels of granularity.

Example#

Let’s assume $$ d_{\text{model}} = 8 $$ (for simplicity), and calculate the position embeddings for $$ pos = 1 $$.

For $$ i = 0 $$: $$ PE(1, 0) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{0}{8}}}\right) = \sin\left(1\right) $$

For $$ i = 1 $$: $$ PE(1, 1) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{0}{8}}}\right) = \cos\left(1\right) $$

For $$ i = 2 $$: $$ PE(1, 2) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{2}{8}}}\right) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{10}\right) $$

For $$ i = 3 $$: $$ PE(1, 3) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{2}{8}}}\right) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{10}\right) $$

For $$ i = 4 $$: $$ PE(1, 4) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{4}{8}}}\right) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{100}\right) $$

For $$ i = 5 $$: $$ PE(1, 5) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{4}{8}}}\right) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{100}\right) $$

For $$ i = 6 $$: $$ PE(1, 6) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{6}{8}}}\right) = \sin\left(\frac{1}{1000}\right) $$

For $$ i = 7 $$: $$ PE(1, 7) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{10000^{\frac{6}{8}}}\right) = \cos\left(\frac{1}{1000}\right) $$

These values are then added to the corresponding token embeddings to provide the model with information about the position of each token in the sequence.

Author

Dr Hari Thapliyaal

dasarpai.com

linkedin.com/in/harithapliyal

Comments: